Mapping this moment

“We don't just build systems for children; children are shaped by the systems we build.”

by Sam Fitzpatrick

Director of Communications

The Reach Foundation

When we speak to headteachers across the country, a single feeling comes through with striking consistency: a growing weight that resists easy explanation.

It isn’t the familiar burden of accountability, nor even the strain of tightening budgets. It is something heavier. It is the sense that the boundary between the school and the world has dissolved, and that schools are now absorbing a tide of societal distress they were never designed to contain.

At The Reach Foundation, we often refer to “the current moment.” It’s a phrase we use to signal that something about this period in British education feels different—more acute, more tangled—yet we haven’t always named exactly what sits inside it. In truth, the term has become a kind of shorthand for a complex reality we haven’t fully articulated.

To understand it, we need a better map. If we want to understand the crisis in attendance, the explosion in mental health needs, the stubbornness of the attainment gap; we need to look beyond the classroom and understand the "ecology" of the child.

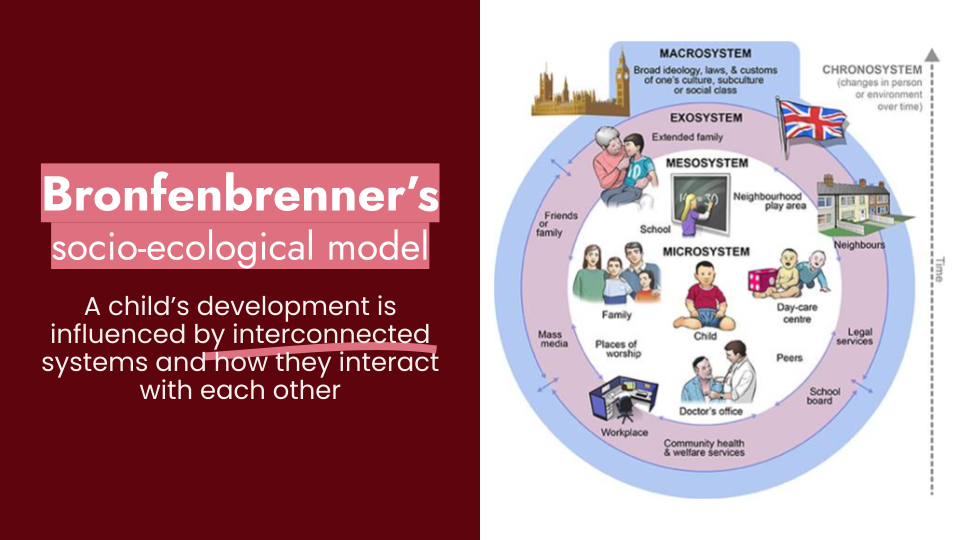

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory provides that map. It helps us see that the challenges in schools are not isolated failures, but symptoms of a single, dysregulated ecosystem.

The chronosystem: Crisis as context, not an event

Bronfenbrenner’s outer ring is the “chronosystem”—the dimension of time.

For the adults running schools, the last five years have been a sequence of shocks: the pandemic, the recovery, the cost-of-living crisis. But for a child in Year 4, this is not a sequence of events; it is their entire conscious life.

The cohort currently moving through primary school were toddlers during the lockdowns of 2020 and 2021. They learned to speak, play, and socialise in a world defined by isolation and parental anxiety.

The BICYCLE study suggests that fewer than six in ten of these children reached expected developmental levels when they started school—meaning in every average reception class, three additional children arrived "beginning behind."

And, crucially, rather than entering a period of recovery, these children have lived through the sharpest fall in living standards since the 1950s. For this generation, crisis is not an interruption to normality; it is the baseline context of their childhood, and this "permacrisis" has created a cumulative load, denying families the "slack" required to recover from one shock before the next arrives.

For education leaders, this means we are not navigating episodic disruption, but developmental disruption, and our current leadership frameworks were not built for that.

The macrosystem: Structural inequity

If we look at the “macrosystem”—the economic and cultural context—we find the engine room of this pressure.

We see people in our community performing acts of daily heroism. We see parents working exhaustive hours, holding families together with love and grit, trying to shield their children from the cold winds of the economy. But resilience has its limits.

The numbers are difficult to process, but we must face them.

4.5 million children in the UK are living in poverty. That is 31% of all children, or nine children in every average classroom of thirty.

Even more concerning is the depth of this inequity: 3.1 million of these children are living in "deep poverty," where the struggle is not just for comforts, but for essentials like warmth and food.

Seven in ten of those children live in a family where at least one adult works. This is not a crisis of worklessness; it is a crisis of everyday precarity. It is a crisis of children watching parents work exhaustive hours yet still struggle to heat the home or put food on the table. That strain travels inward. It shapes sleep, stress, bandwidth, executive function. It makes “readiness to learn” a structural, not behavioural, issue.

What’s more, we know that the “macrosystem” distributes this poverty along distinct fault lines of race, family structure, and disability, revealing systemic inequities embedded in the social fabric (all data from CPAG, 2025).

For education leaders, this means that academic leadership cannot be separated from economic reality. The “macrosystem” seeps into every classroom interaction. It’s hard to “regulate the temperature in the classroom” when there is a fire burning outside the gates.

The exosystem: The hollowing out of support

Perhaps the most acute pain point for school leaders lies in the “exosystem”—the services and structures that are supposed to scaffold the family.

In a healthy ecosystem, this layer acts as a buffer. When a child is in distress, the school refers them to specialist support (CAMHS, social care, early help). Today, that scaffold has buckled.

The statistics describe a system in paralysis. In 2023/24, 78,577 young people waited more than a year for CAMHS treatment. The average wait time was 392 days. More damning still, over 170,000 referrals were closed before the child ever accessed support.

This creates the "referral loop." A child is referred, waits, and is bounced back to school because their needs are "too complex" for early help but "not severe enough" for acute services. The school becomes the insurer of last resort.

The mesosystem: Fraying connections

The “mesosystem” describes the connection between a child’s worlds, especially between home and school.

That connection is fraying. The most visible metric of this fracture is the rise in severe absence. The number of children missing more than 50% of school time has risen by 167% since 2019, creating a population of over 160,000 ‘ghost children’.

We must be careful not to frame this simply as "truancy.” It is often an ecological rejection of an environment that feels unsafe or unresponsive. Research on "institutional betrayal" highlights how parents of children with SEND often experience the battle for support as adversarial and, sometimes, traumatising.

When families feel let down by the very institutions meant to support them, trust evaporates. 50% of parents now believe that missing a day of school a fortnight is "reasonable". This is not deviance; we are witnessing the breakdown of the social contract that held our education system together.

For education leaders, this means the work is no longer merely to enforce attendance policies, but to rebuild the relational contract that attendance rests upon.

The microsystem: The classroom as a mirror

Finally, we reach the “microsystem”—the classroom.

This is where the failures of the outer rings make contact with the child. This is where the "ecological debt" is collected.

Data from the Education Policy Institute shows that the entirety of the increase in the "disadvantage gap" since 2019 can be explained by disadvantaged pupils missing time in school.

The logic is inescapable. The classroom gap is driven by absence. Absence is driven by unmet health needs (exosystem) and poverty (macrosystem). What shows up in the classroom is not simply a matter of pedagogy, but ecology.

A moment that demands a different kind of leadership

This diagnosis, this map, is heavy. But naming it matters.

It helps us see that the pressures leaders face are not personal failures or professional shortcomings; they are the predictable outcomes of a system under strain.

If we treat the current crisis as a technical problem—one that can be fixed with a new attendance tracker, a stricter behaviour policy, or a better curriculum resource—we will fail. That is, if we misread this ecological problem as an operational one, we will reach for the wrong tools. But if we see “the system” as it actually is—a deeply human, relational, interdependent one—a different kind of leadership becomes possible.

If the problem is ecological, the solution cannot be isolationist. We cannot just "run the school"; we must learn to convene upstream, to repair the connective tissue linking different systems, and to design new ways of working that acknowledge the reality of children' s lives as they are—not as we wish them to be.

This edition of our Fieldbook explores that leadership.

From my exploration of adaptive leadership, to Leonie’s insights on living systems, to Shelley’s exploration of imagination and agency, each piece turns one facet of this challenge into something leaders can actually work with.

As you read the essays that follow, we invite you to hold this map in mind. Our task, collectively, is to build a form of leadership capable of putting the pieces back together.

We don't just build systems for children; children are shaped by the systems we build.