The mismatch: When vertical systems meet horizontal lives

Imagine a school that is absolutely nailing it.

It’s the living embodiment of the NPQ framework. A high-fidelity realisation of Ofsted’s framework. The children are making steady academic progress, and the adults are thriving, too.

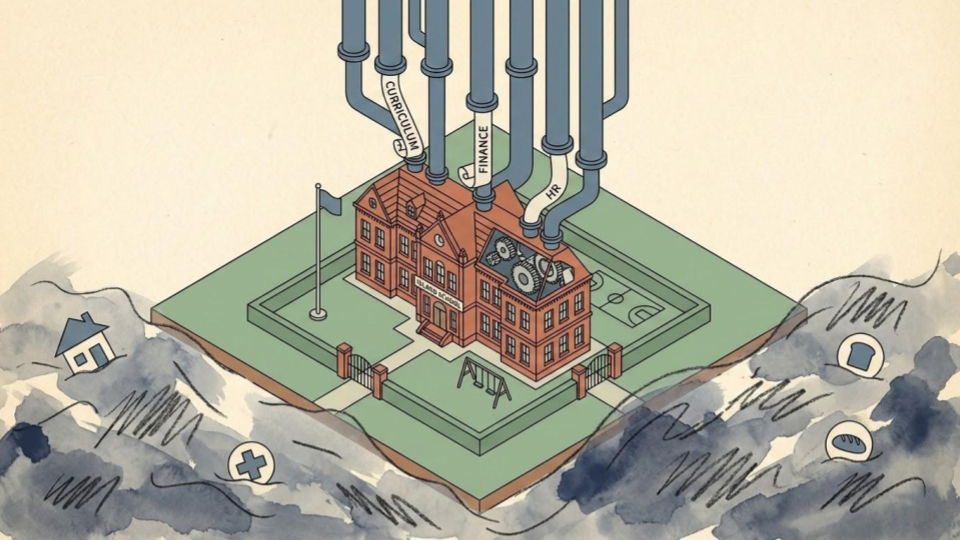

Inside the gates, the school hums like a well-oiled machine. The curriculum accounts for everything we know about cognitive development, meticulously sequenced to build long-term memory. The “warm-demanding” culture ensures a calm, predictable environment where every minute is optimised for learning.

As part of a high-performing trust, the school draws expertise from an elite central services team: clinical financial planning, centralised HR support, and weaving all sorts of tapestries with the “golden thread” of professional development.

Would this be enough?

In other eras, including eras that probably still feel relatively fresh in the minds of our profession, the answer is probably ‘yes.’ A school like this—in the late naughties, for instance—would be an undisputed success story. But in 2026, even those schools approaching the level of optimisation outlined above are struggling.

Despite the internal rigour, attendance hasn’t returned to pre-pandemic levels. Despite the high-quality and continuously improving teaching, the volume and complexity of SEND is rising—over 1.7 million students in England have special educational needs (DfE, 2025).

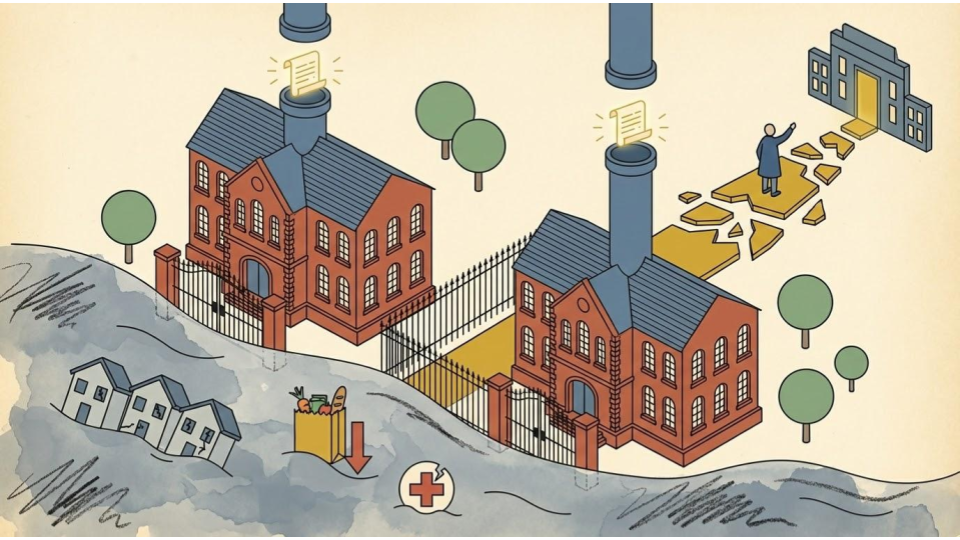

The island of order is being swamped by a rising tide of housing instability (Shelter, 2025), food insecurity (The Food Foundation, 2025), and a mental health crisis (BMA, 2025).

While the school’s outcomes are strong and improving consistently year on year—at this school, all student groups are making above average progress and attaining well—there’s been a marked increase in alumni struggling to secure meaningful post-school opportunities. Nationally, one in eight 16-24 year olds are not in education, employment, or training (ONS, 2025)—and this school has seen its share rise in recent years, too.

It’s becoming clear that in order to secure lives of choice and opportunity for all babies, children and young people, great schools are necessary but not sufficient.

Is there another way?

At The Reach Foundation, we are hopeful. Every day, we see the extraordinary dedication of leaders unwilling to accept the current situation as an inevitability.

We know that within our communities, there is enough ingenuity, care and expertise to ensure our young people can thrive.

However, we also believe that this intent, no matter how pure, must be matched by a firm and sustained commitment to a new way of working. Hope is great fuel, but it’s not a strategy.

We can’t just care our way out of this. If we continue to pour all of that energy into a system that is structurally misaligned with the lives of children and young people, our most ambitious efforts will stall.

Our current model is established around a vertical logic. The plumbing is designed, for good reason, to move power, decision making, accountability and expertise up and down a closed chain: school <> trust <> government.

At the right scale, centralised functions can secure significant economies of scale, increasing the number of pennies in every pound that end up directly benefiting children. This approach also offers central government a neat way to track and manage the performance of schools; providing accountability to taxpayers and insight into which schools and trusts might need support and when.

But it also means that sometimes we end up with two schools on the same road operating in complete isolation from one another. Structurally, they might share a fence, but not much else.

The problem with this structure is that children don’t live in trusts; they live in neighbourhoods.

That, while this verticality can be an incredibly powerful tool for institutional efficiency, this structure is blind to the horizontal lives of children—the stuff that happens “outside.”

The 80/20 fallacy

A reasonable sceptic might ask:

But if children only spend 20% of their waking hours in school, why should we try to “take on” the other 80%? Is this not mission creep?

The first reason is foundational. You cannot teach a hungry child.

The 20% of time that children spend with us in our schools is influenced hugely by what happens during the 80% of time they spend outside.

If a child is affected by housing instability or struggling with anxiety, the technical tools of the classroom—the retrieval practice, the dual coding—lose their efficacy.

The second reason is economic.

When we ignore these issues, intentionally or otherwise, we end up generating significant ”failure demand”.

We introduce additional friction into the system and, as a consequence, end up spending a disproportionate amount of our time and money on downstream interventions and crisis management.

The third reason is part structural, part moral.

In many communities, our schools are often perceived as the most visible, accessible and/or trusted “safe harbour.”

This means that, while a child only spends 20% of their time with us, it’s more often than not the place where the challenges with roots in the other 80% of their time become visible to us.

We have an obligation to acknowledge these and respond.

Has anyone solved this?

Of course, we are not the first sector to hit this wall. For decades, our National Health Service operated on a similar vertical logic.

Large hospitals specialise in specific conditions and technical fixes. Patients are “referred up.” Individual departments are getting better and better all the time at treating well-defined conditions, but are more disconnected from the patient’s broader, horizontal life (diet, lifestyle, social isolation, etc.).

Their solution is a combination of Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) and Integrated Neighbourhood Teams (INTs). ICBs are statutory organisations responsible for the strategic planning and funding of health services across a large geographic area. INTs are front-line, collaborative, multidisciplinary teams that provide direct, coordinated care at the local level.

Crucially, INTs do not report to the same CEO; they are structurally bound and motivated by the shared fate of a common postcode. Their goal is not to optimise the efficiency of their individual surgery, for instance, but to improve the health of people within their community.

The pivot

We do not need to dismantle schools and trusts. We should encourage our schools and trusts to rewire the utilities within their communities. We should complement the system’s prevailing vertical accountability with horizontal, civic connectivity.

That requires leaders to shift from institutional interest to neighbourhood interest, underpinned by the concept of ‘shared accountability, differentiated responsibility’ as articulated by colleagues at StriveTogether.

It requires a deliberate shift away from valorising “heroic leaders” (singular figures who “save” children) and towards a notion of “civic architects.” Local leaders who look at the whole “site” of a child’s neighbourhood and ask:

How do we build the permanent infrastructure of opportunity that every child here needs to thrive?

Organising around place isn't "extra work." It is structural relief. By building horizontal bridges between our institutional islands, we can pay down the "ecological debt" of the disadvantage gap. It’s an approach that will support us to move from acts of charity to acts of citizenship.

In the following articles, we’ll explore what this looks like in practice.

by Sam Fitzpatrick

Director of Communications

The Reach Foundation