Staking the ground

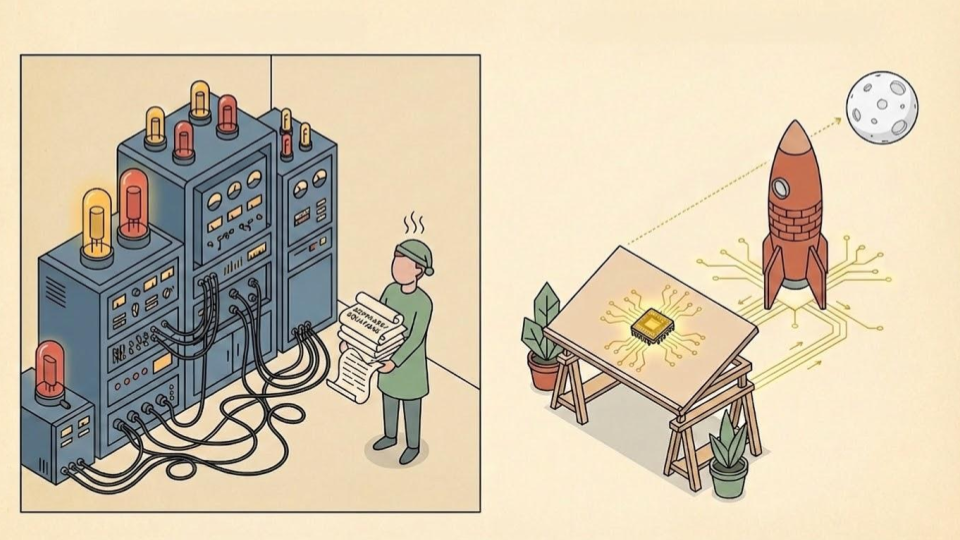

We had the software to put man on the moon a fair while before we did.

We’d solved whatever equations needed solving, developed the necessary software, and established the collective will to make it happen.

But there was a problem: we didn’t have the hardware. The heavy, vacuum-tube computers of the era were far too big to travel, and couldn’t host the code required for such a journey anyway. It took a radical leap in hardware development (the invention of the integrated circuit) to catch up with the ambition of the visionary software.

In this article, we want to make the case that we’re facing a similar hardware challenge in education today.

We see leaders every day who possess the right software. They are deeply committed to their communities; they see the whole child and want to collaborate with others. But it’s hard going, because we are trying to run this sophisticated, relational software on outdated hardware.

The result of this mismatch is a culture of “beating the odds.”

We celebrate the heroic headteacher or the resilient young person who succeeds in spite of a fragmented landscape. Of course, we should celebrate occasions where somebody exceeds expectations, but “beating the odds” is a tacit admission that the game is rigged. When success relies on extraordinary effort to overcome an ordinary failure of design, the system is broken.

We believe it is time to move beyond these heroics. We want to stop asking leaders and children to “beat the odds” and empower local leaders to “change the odds” in their favour instead. To do that, we need to upgrade the hardware. We need a new technology that allows us to shift from institutional isolation to neighbourhood connectivity.

We have been calling this hardware “the cluster.”

What is a “cluster”?

We define a “cluster” as,

“a formal, structural alliance of schools and local partners serving the same children and families within a clearly defined geography”.

“Cluster” is a funny sort of word. What does it mean?

In truth, we’ve sort of stumbled into it at Reach—maybe there’s a better word—but it’s stuck. We think it’s stuck because it works; it encapsulates something approaching a natural law in social ecology.

Without this structural alliance, our best intentions remain trapped in institutional silos. We see “transition fractures” where progress is lost between primary and secondary, engagement falls between key stages, and “postcode lotteries” of provision.

We see the cluster as the bridge that resolves the tension between agency and structure. As Anthony Giddens argued, social structures aren’t just barriers that constrain us; they are very things that enable our actions.

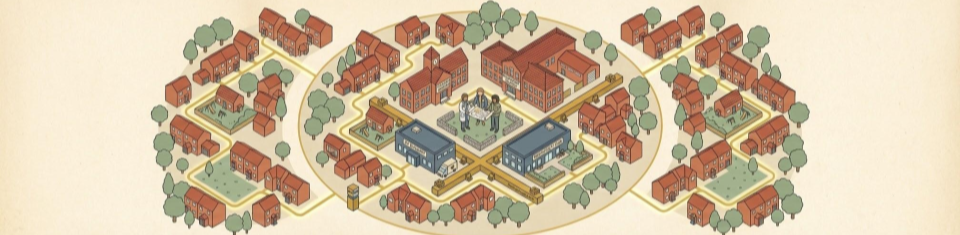

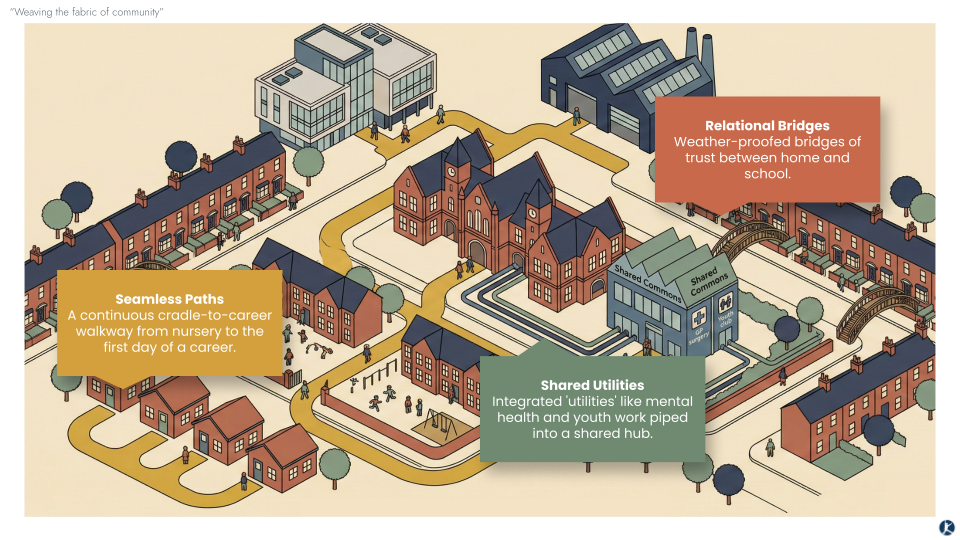

In this sense, a cluster is the formal hardware that allows the software of our shared values to actually function, transforming the neighbourhood from a collection of isolated actors into a coherent, capable system.

How big is a cluster?

What is “a neighbourhood”? How big is “a community”? When we say “place,” what scale are we talking about?

The answer is, of course, it depends.

But we believe the optimal “unit of delivery” is, in most cases, probably something like the “postcode district”.

For example, that’s B10 (in Birmingham), FY1 (in Blackpool), BD5 (in Bradford), HU3 (in Hull), DE23 (in Derby), CO15 (in Clacton-on-Sea), EX5 (in Exeter), or PO6 (in Portsmouth)—to pick a handful from a more than 3,000 in the UK.

These are places that people identify with.

While administrative boundaries or local authority lines can sometimes feel like arbitrary marks on a map, a postcode district (despite being exactly that), usually carries the weight of a real identity. It’s the answer people give when somebody asks where they’re from.

It represents a geography that is legible to people living within it, and recognisable to people who don’t. Like any rule of thumb, there are exceptions, but it’s a fairly solid starting place in our experience.

It’s large enough to contain a child’s entire cradle-to-career journey, yet small enough to still feel like home. We can stake our ground at this level. We can design infrastructure at this level to guarantee better experiences and outcomes for all babies, children and young people.

Why this size?

We think the “postcode district” represents a “Goldilocks” scale of social ecology. It’s a scale that is large enough to be efficient but small enough to remain relational. There are some very practical reasons for working at this scale, too.

First, this scale makes sense to people. It already exists. The postcode district aligns with the “15-minute neighbourhood”—the geographic radius where a family’s daily life (nursery, school, GP, shops) happens. By matching our hardware to this lived reality, we align the system with the child’s “ecological map.” We aren’t asking families to navigate a distant regional bureaucracy; we are building support exactly where they already walk.

Second, it creates a “relational estate.” Because the geography is contained, the professional network becomes dense. At a population of roughly 20,000 people, GPs, headteachers, and social workers can know one another by name. We move from anonymous, digital referrals towards something more akin to a “village square” dynamic, where strong, trusting relationships allow us to move faster than bureaucracy.

Third, it enables “service agglomeration.” This density makes the system viable. There is a critical threshold—a “tipping point” of need—where it becomes economically possible to meet emerging needs. Instead of diluting a mental health clinician’s impact across an entire city, or leaving them hidden in a distant hospital, the postcode scale allows us to anchor them in a shared local hub. We achieve the efficiency of a large system with the precision of a local one.

So what does it look like? And what does it do?

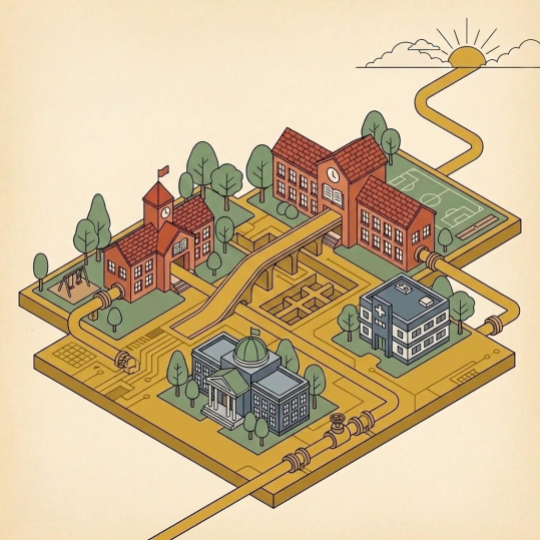

If the cluster is the hardware, the “Prosperity Grid” is the service it provides.

To understand the grid, we first have to consider how our definition of “progress” and “success” is evolving. Once upon a time, there was a single, linear path to a “good life”: GCSEs, to A-Levels, to university. Over the last 15 years, that path has fragmented. Young people are being offered an increasing amount of choice. While the established route is still right for many, we now see a diversification of options, from degree apprenticeships to technical vocations.

However, we are still largely focused on managing the paths. The prosperity grid is something different. We aren’t just looking at the individual tracks; we are focused on securing the enabling conditions that allow all children to enjoy lives of choice and opportunity, regardless of which path they take.

To build this, local leaders weave three essential threads of connectivity into their communities:

Seamless Paths (Educational Coherence): A continuous cradle-to-career walkway from nursery to the first day of a career. It means that nurseries, primary schools, secondaries, colleges—mainstream, special and alternative provision—work as one.

Relational Bridges (Consistent Relationships): These are the weather-proofed bridges of trust between the front door and the school gate. It involves moving beyond “parental engagement” towards “belonging,” ensuring that when a family faces a storm, the connection to support remains open so that the path to the classroom remains secure.

Shared Utilities (Connected Local Systems): This is the neighbourhood operating as a fully integrated utility. Specialised services—mental health support, youth work, social care—are “piped” directly into shared local hubs where families already are.

What are the benefits of this approach?

Structural relief for leaders. Population-level change for children.

For leaders, it’s about moving from “heroic effort” towards “strengthening capacity.” By building a shared grid, individual leaders and institutions are no longer the sole bearers of the community’s weight. When a family is in crisis, the system responds.

For children, it’s about choice and opportunity. We want to ensure that every baby is well-supported in their first 1,001 days. We want to ensure that every young person has a meaningful post-school destination.

We should track these outcomes at a population level—for example, all children in a specific postcode district—to ensure that we aren’t just helping a lucky few to “beat the odds,” but that we are successfully “changing the odds” for an entire generation.

What does it look like in practice?

Restoring this architecture is not a “plug and play” intervention. It’s a generational commitment to civic engineering. However, it’s also true that the dividends of this work begin to appear from the moment the first “wires” are (re-)connected.

We support our Cradle-to-Career Partners to work through a three-phase journey. You’ll find links to three case studies of partners at different stages along the way:

Wythenshawe

Newquay

![260209 TRF—Fieldbook #3 [v1] (2).png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6560bcf40f7abd1c100aeb81/1770666840079-FOK8TE564SH58HBYGTC3/260209+TRF%E2%80%94Fieldbook+%233+%5Bv1%5D+%282%29.png)

![260209 TRF—Fieldbook #3 [v1] (6).png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6560bcf40f7abd1c100aeb81/1770666840105-J6SFJK261EEI52BZOYXM/260209+TRF%E2%80%94Fieldbook+%233+%5Bv1%5D+%286%29.png)

![260209 TRF—Fieldbook #3 [v1] (3).png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6560bcf40f7abd1c100aeb81/1770666841181-2SJV48GPQPQHH8GYN5TX/260209+TRF%E2%80%94Fieldbook+%233+%5Bv1%5D+%283%29.png)

Where would you plant your flag?

In recent years, we’ve been encouraged by the direction of travel within the sector, with central and local government, school trusts and federations, all encouraging schools to form local groups. But permission alone is not a plan. If we simply create smaller administrative silos, we could repeat the mistakes of the past.

Restoring neighbourhood outcomes is not a matter of bureaucratic shuffling. By creating new structures—clusters—we choose to treat our collective time and relationships as capital to be invested, rather than a cost to be managed.

If you are a leader moved by this vision, we invite you to begin the process of identifying your site. In the comments below, share the postcode district (e.g. WV10, OL1, NR31) where you see the greatest potential to do this work.

Let this be a space to map where ambition is growing, where our goals align, and where—neighbourhood by neighbourhood—this new hardware can take shape.

by Sam Fitzpatrick

Director of Communications

The Reach Foundation